All That Glitters is Not Gold: Bookbinding with Mother of Pearl

- Jordan Costanza

- Nov 25, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 14, 2020

On their own, mollusks are not a particularly engaging creature on which to focus. The snails and shells they define are often a dull, muted family. Their glitter, however, lies beneath the surface—quite literally. The opalescent shell that lines a mollusk's innards is called nacre, otherwise known as mother of pearl. Mollusks wield mother of pearl (nacre) as a highly successful defense mechanism against foreign invaders that manage to slip inside the shell. However, once inside, the mollusk coats the intruder with layers upon layers of nacre until it is successfully incapacitated. Thus, the body of the pearl is formed with the corpse of an encroacher and its shell is hardened (and beautified) with layered nacre.

Nacre is deceptively strong. While the process of its formation is not wholly known, Dr. Pupa Gilbert, a physicist of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says that "[y]ou can [run] over it with a truck and not break it." Mother of pearl's near-indestructibility is not its only selling point. Its pearly iridescence has long fascinated the eye, which has encouraged bookbinders to utilize it in their practice as an ornamental element.

The mollusk's introduction into literary history was by way of Jacques Barbut's taxonomic publication Genres des Mollusques in 1783. Though originally written in French, the text was later reprinted in English as Genera. In fact, it was this translation that first introduced the word "mollusk" into the English language from the French mollusque, though the modernized spelling of "mollusk" did not come until 1832.

REMOVING THE MOTHER OF PEARL

The modern process of extracting mother of pearl from its mollusk host is a careful one. Nacre is extremely durable, meant to stand up to even the toughest of mollusk adversaries. Because of its strength, scientists have created an “aqueous hydrochloric acid solution” process that gradually breaks down the calcite and protein layers that protect the layers of nacre beneath. This process is repeated as many times as needed until the necessary layers are broken down and the nacre can be removed intact. The tediousness of the removal process (as well as the fact that it must be done by hand) is what has made mother of pearl an attractive but relatively scarce means of decoration. This scarcity, of course, has contributed to its value throughout history. In the nineteenth century, when mother of pearl bookbindings were at their highest demand, extractors likely had to make do with metal tools, which would not only be difficult but would also risk the integrity of the shell.

BOOK BINDINGS

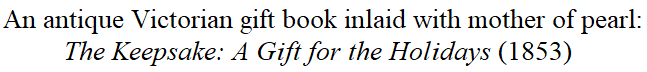

Mother of pearl bindings reached peak popularity in mid to late nineteenth-century United States when “gift books” were in vogue. Meant to be an impressive showing of largesse, gift books were popular texts, often fiction—from authors such as Lydia Marie Child, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Edgar Allan Poe—that were beautifully engraved and decorated in various “novel” mediums: papier mâché, “embossed morocco, textured cloth, decorated papers and even mother of pearl.” Though this trend also helped to expand the reach of these literary texts, its marketability was found in its beauty.

Gift books were produced for reading and display, and as such, the practice of their decoration was precise and ornate. The very first gift book in the United States (which included American literature and not solely English reproductions) was created by Philadelphia publishers Carey and Lea in 1825. Their text was an immediate success, which quickly set off a craze of copycats who wished to capitalize on the same potential earnings. For almost thirty years, the gift book was largely given within romantic relationships, especially in courtship rituals. And as such, the binding of the book would need to reflect the romance between the giver and the receiver. With its symbolism of agape, luck, and prosperity, it was the perfect "gemstone" gift to exchange between lovers. In addition to courtships, these books were also popular for special occasions like birthdays and holidays.

Instantly recognizable by its unique opulence, mother of pearl was a popular choice for gift book ornamentation; and it was often used in conjunction with other materials, papier mâché particularly. Full bindings done in mother of pearl were rare, often saved for religious texts. Instead, cover engravings were inlaid with chips of the material as small highlights.

Today, mother of pearl is a less likely material to be used, as, with the passing years, it has become considered "déclassé." It has retreated back into obscurity after its fall from grace and now appears mostly in jewelry and decorative trinkets. Though mother of pearl has appeared in the practice of bookbinding as far back as the Ottoman Empire, it has now become a lost art. No longer do we see books inlaid with its luster or entire covers forged of its unique sheen. It is sadly a relic of bookbinding days past. However, its artifacts still circulate in book lover and rare book collector circles to this day—ultimately allowing them a second, third, fourth, nth chance at life in the spotlight.

Further Reading

"On the mechanics of mother-of-pearl: a key feature in the material hierarchical structure" by F. Barthelata, H. Tanga, P. D. Zavattierib, C. M. Li, H. D. Espinosa, in Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids

"Creating a World of Books, Friends, and Flowers: Gift Books and Inscriptions, 1825-60" by Cindy Dickinson, in Winterthur Portfolio

"NEW IDEAS IN FRENCH BOOKBINDING 1914-1939" by Felix Marcilhac, in The Bulletin of the Decorative Arts Society 1890-1940

The British Library guide to bookbinding: history and techniques by Philippa J. M. Marks

"The Art of Bookbinding in the Ottoman Empire (Fifteenth to Nineteenth Centuries)" by Fatih Rukanci and Hakan Anameric, in Bibliological Studies of Torun

Comments